Hoboken in WWI

A City in Wartime: Hoboken, 1914-1919

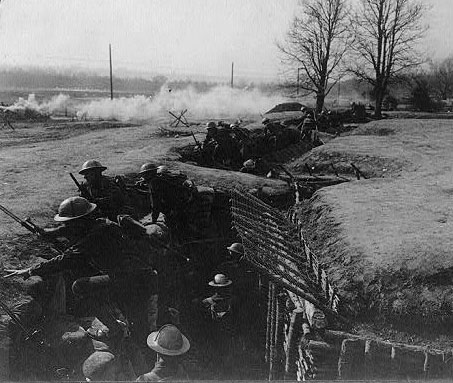

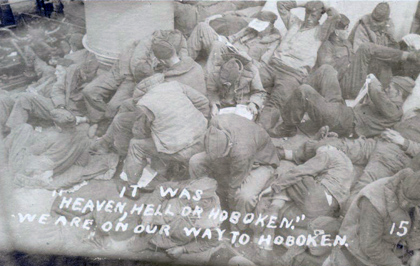

In the summer of 1914, Europe went to war. Although the United States did not enter the Great War until the spring of 1917, the conflict that would later be called World War I had an immediate impact on Hoboken, a port city with large immigrant communities. When America formally entered the war on April 6, 1917, Hoboken’s waterfront became central to the war effort as the port of embarkation for thousands of American troops. “Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken” became a slogan for troops hoping for a safe return home. The war brought major changes to life in Hoboken, and the city would not be the same after the war.

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was touring Sarajevo, capital of the Empire’s province of Bosnia. A team of assassins was waiting to kill the archduke, and one of them, Gavrilo Princip, succeeded. The assassins had ties to organizations that wanted Bosnia to be joined with the kingdom of Serbia. The Austro-Hungarian government, reeling from the assault on its national pride and frightened by Slavic nationalism, held Serbia responsible.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand set in motion a chain of events that would lead to the outbreak of war by the first week of August. The Central Powers of Austria-Hungary and Germany (joined in November by the Ottoman Empire), faced off against the Allies of Russia, France, and Great Britain. Europe’s complex system of alliances, years of military preparedness anxiety, national leaders’ fear of backing down and appearing weak, and the widespread view that a European war would be brief (and likely an opportunity for national and personal glory) all contributed to the outbreak of the war. [1]

Initially, most Americans were happy to be detached from the war. There was a tendency for immigrants and alien residents to identify with their old countries. This meant that some German-Americans and Irish-Americans had little sympathy for Britain. [2]

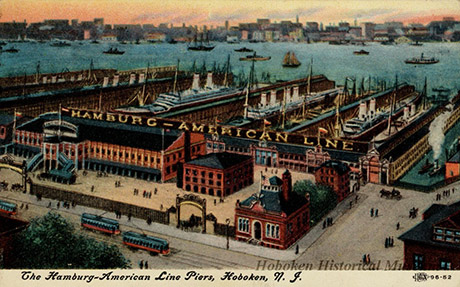

The war’s effects were immediately felt in Hoboken, which was home to major European shipping companies and numerous immigrants and foreign nationals. At the outbreak of war, the powerful British Royal Navy acted quickly to blockade Germany. British warships rounded up German merchant vessels or drove them to port. A number of German ships were in port in Hoboken, the American home of the Hamburg American and North German Lloyd steamship lines. The ships would remain stuck in port until the American military seized them in 1917. [3]

While many Hoboken jobs were lost by the blockade of European liners and the sharp decline in transatlantic migration, other businesses in town profited from the war. While the German ships sat in port, other ships were needed to make trips to Britain, and Hoboken shipyards prospered. Two wartime needs – munitions and paperwork – were supplied by Hoboken shops, at the factories of the Remington Arms Company and American Lead Pencil. [4]

While many Hoboken jobs were lost by the blockade of European liners and the sharp decline in transatlantic migration, other businesses in town profited from the war. While the German ships sat in port, other ships were needed to make trips to Britain, and Hoboken shipyards prospered. Two wartime needs – munitions and paperwork – were supplied by Hoboken shops, at the factories of the Remington Arms Company and American Lead Pencil. [4]

America’s trade with the Allies, especially in munitions, raised tensions internationally, and these tensions were felt locally. Before America’s entry in the war, several Germans from Hoboken were arrested on suspicion of sabotage and related activities. A German citizen named Fritz Kolb was arrested in his room in the Commercial Hotel at 212 River Street in March 1917, and convicted a month later for possession of explosives. [5]

While the United States was officially neutral in 1914, the country had significantly more trade ties with Britain than it did with Britain’s enemies. As Britain and Germany both tried to prevent supplies from reaching their enemy by sea, tensions between the US and Germany escalated. The loss of American lives to German submarine (u-boat) attacks turned American public opinion against Germany.

In early 1917, the United States and Germany were on a collision course. Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, where any ship approaching Britain in international waters could be subject to attack without warning. Tensions were brought to a head with the release of the Zimmermann Telegram, a coded message from the German government to Mexico proposing an alliance against the United States if open war broke out. The telegram included the enticement that Mexico was to reclaim territories lost to the United States in the 1840s. Submarine warfare and the Zimmermann Telegram were the major issues raised by President Woodrow Wilson when he went to Congress to request a declaration of war against Germany in April of 1917. On April 6, a declaration of war was passed. [6]

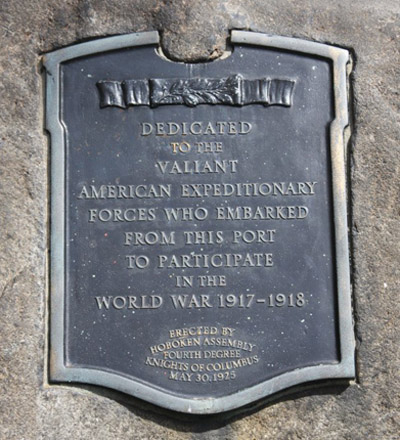

Hoboken’s central role in America’s war effort was immediately established. Hoboken was declared the main point of embarkation for the United States Expeditionary Force, as the forces heading to fight the war in Europe were called. Hoboken took a proud place in the American war effort, but many of the city’s residents and business owners would face hardship during the war. [7]

Imperial Germany was now officially the enemy, and a number of German ships were sitting at the Hoboken docks. At dawn on April 6, 1917, US Army soldiers seized the German ships as they sat in port. Two weeks later the German shipping companies’ piers were taken over by the government and army encampments were established there. The prize ships of the Hamburg-American and North German Lloyd lines were turned into massive troop transports. [8]

In the tense atmosphere of war, where suspicions ran high, German people living in the United States were immediately targeted as potential or actual enemies. [9]

The large German population of Hoboken was harshly affected. According to the 1910 US Census, Hoboken had a total population of 70,324 people, of which 10,018 were German-born. [10] Over the course of the war, many of Hoboken’s Germans were detained, evicted from their homes, lost their jobs, or saw their businesses shut down. High-level employees of the German shipping companies were among those arrested shortly after America’s entry into the war. While Irish Americans generally remained cold toward Great Britain, they were able to maintain their position in American society. In contrast, the structure of Hoboken’s German community was dismantled in the nineteen months of war, and Hoboken would no longer be a German town. [11]

Hoboken, known internationally as a port of entry to America, now became famous as a port of departure for European war. The slogan “Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken” was taken to Europe by the “doughboys” of the American Expeditionary Force. General John J. Pershing, commander of the AEF, is credited with coining the slogan when he told departing troops that they would be in “Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken” by Christmas, Hoboken being the port that nearly all soldiers would pass through on their way home. [12]

The first convoy carrying American troops to war left Hoboken on June 14, 1917. Fourteen transport ships, carrying 11,991 officers, enlisted men, and civilians departed the city. A total of 936 voyages to France and England were made from Hoboken during the war. [13] Approximately two million servicemen passed through Hoboken between the spring of 1917 and the fall of 1918. [14]

Many troops were brought overseas in German ships that had been captured in Hoboken. Among these ships was the USS Leviathan, formerly the Hamburg-American liner Vaterland. The 58,000 ton Leviathan was the largest ship in the world at the time. The Navy repainted the ship in gray and converted the prestigious liner to a troop transport with a capacity of 14,000 passengers. In 1918 the Leviathan was repainted with a dazzle camouflage pattern, designed to make it difficult for German u-boats to target. Over the course of the war Leviathan delivered 120,000 servicemen to Europe. [15]

Daily life in the partially militarized city of Hoboken was significantly affected by the war. Although wartime industries created new jobs, wartime activity caused major economic disruption and the city experienced an overall decline as a result of the war.

Daily life in the partially militarized city of Hoboken was significantly affected by the war. Although wartime industries created new jobs, wartime activity caused major economic disruption and the city experienced an overall decline as a result of the war.

Dockworkers and shipyard workers were fired en masse for being born in one of the enemy nations. Thousands of German, Austrian, and Hungarian workers, including American citizens, lost their jobs. A federal order prohibiting enemy aliens from living, working, or traveling within one hundred yards of docks, piers, and waterfronts caused thousands of evictions on Hudson and River Streets. A major point of conflict between the local and federal government involved the sale of alcohol. Hoboken was famous for its saloons and beer gardens, many of which were near the waterfront. Local officials dragged their feet in complying with federal regulations on serving alcohol near the military areas, but eventually the federal government prevailed. In March of 1918 the military took greater control over Hoboken life. Women found walking the streets after dark faced arrest for prostitution, and Chinese restaurants were ordered to close nightly, causing many to go out of business. [16]

Judge Charles DeFazio, Jr recalled a bit of the disruption that the War years brought Hoboken, but also remembered the excitement and pride inspired by the troops marching through the street on their way to the docks. DeFazio recalled that troops got out of trains on the west side of town and marched through First Street to the docks.

They’d all line up, the soldiers would parade up First Street and get their greetings and everything. The people were so kind to them and they were so nice to people. And they’d walk up, that’s a stretch, that’s about 14 blocks, 12 or 14 blocks. All the way up to the river. Get onto the pier site. And that’s where they’d enter the ships eventually. That’s where the Army transports came into these piers to take those boys across the ocean to the warfront, in France. And I well remember, it was 1917, or thereabouts.

That gave we youngsters in Hoboken, especially the boys, an opportunity to voluntarily serve these troops. We kids that were high school age. We loved the troops and the troops loved us. And on the counterpart, of course, the Navy…and we used to serve the sailors too. They’d have knapsacks [which we’d carry and get some money.] [17]

After armistice was declared on November 11, 1918, celebration and mourning alternatively took hold at the Hoboken docks as ships returned homesick soldiers as well as caskets containing the remains of the fallen. More than two million American soldiers had fought in Europe, including 2,469 draftees from Hoboken.[18] Over 50,000 Americans died in combat, and thousands died from disease. [19] The first troops to return to America arrived in Hoboken on December 2, 1918. [20] General Pershing triumphantly returned to Hoboken aboard the USS George Washington on September 8, 1919. [21] On November 13, 1919, the Lake Daroga docked in Hoboken, carrying the first transport of the bodies of fallen American soldiers. [22]

The first troops to return to America arrived in Hoboken on December 2, 1918. [20] General Pershing triumphantly returned to Hoboken aboard the USS George Washington on September 8, 1919. [21] On November 13, 1919, the Lake Daroga docked in Hoboken, carrying the first transport of the bodies of fallen American soldiers. [22]

President Woodrow Wilson also embarked from Hoboken for his service in Europe, defining the terms of peace at Versailles. His return in July of 1919 was a time of celebration, as people crowded along Washington street to wave American flags and watch the president pass in his motorcade.

After the war, Hoboken made the rough transition to peacetime felt throughout the country. The Leviathan was turned over to an American shipping company and commercial life returned to the docks.

Hoboken occupied a central place in America’s First World War. America’s involvement in the great conflict was launched from piers that have since been removed or turned into grassy parks where families can enjoy a peaceful afternoon. While the horrors of the war were experienced in faraway fields or in doomed ships on the open sea, bits and pieces of the conflict’s disruptive nature were felt in the docks, tenements, and streets of Hoboken.

Footnotes:

[1] Keegan, The First World War, 48-50, 66-70, 215; The Great War: Timeline.

[2] Zieger, America’s Great War, 14.

[3] Zieger, 11.

[4] Ziegler-McPherson, Immigrants in Hoboken, 102.

[5] Ziegler-McPherson, 104.

[6] Zieger; State Dept.; Keegan, 350.

[7] Ziegler-McPherson, 101.

[8] Ziegler-McPherson, 105-106.

[9] Zieger, 198.

[10] Ziegler-McPherson, 95-96.

[11] Ziegler-McPherson, 101-104.

[12] “Heaven Hell or Hoboken,” HHM.

[13] Hans, 100 Hoboken Firsts, 84.

[14] Ziegler-McPherson, 108.

[15] USS Leviathan, Navy.

[16] Ziegler-McPherson, 108, 111-114, 115, 117.

[17] Hoboken: Circus Maximus at All Times, HHM.

[18] Ziegler-McPherson, 110.

[19] WWI Casualty and Death Tables, PBS.

[20] Ziegler-McPherson, 120.

[21] HHM Website.

[22] Hoboken Bicentennial Calendar.

Sources and Further Reading:

American Entry into World War I, 1917. U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/wwi

B+W photo of Gen. John J. Pershing with Rodman Wanamaker on Hoboken pier, Sept. 8, 1919. Description. Hoboken Historical Museum. http://hoboken.pastperfect-online.com/32340cgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=65494499-050B-4835-B1FF-343356560784;type=102

Destination Hoboken: The Great Ocean Liners of Hamburg-American & North German Lloyd. Hoboken Historical Museum, 2002. PDF download available from HHM Collections. http://hoboken.pastperfect-online.com/32340cgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=ABCEBAD3-71E5-4590-A994-235155541987;type=301

Hans, Jim, 100 Hoboken Firsts. Hoboken Historical Museum, 2005. http://hoboken.pastperfect-online.com/32340cgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=7644F567-D3AA-4286-B48F-322389027300;type=201

Heaven, Hell, or Hoboken, Hoboken Historical Museum Exhibit. https://www.hobokenmuseum.org/exhibitions/main-gallery/past-exhibitions/heaven-hell-or-hoboken-2008-9

Hoboken Bicentennial Calendar. http://hoboken.pastperfect-online.com/32340cgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=DD309C23-7EBC-4D23-9986-865478243854;type=101

Hoboken: Circus Maximus at All Times. Recollections of Judge Charles DeFazio, Jr. Vanishing Hoboken: The Hoboken Oral History Project. Friends of the Hoboken Public Library and the Hoboken Historical Museum, 2002. http://hoboken.pastperfect-online.com/32340cgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=83544553-6B52-4982-B898-213052407393;type=201

iWonder: How Did an Artist Help Britain Fight the War at Sea? BBC, 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zty8tfr

Keegan, John, The First World War, Alfred A. Knopf, 1999.

Teaching With Documents:The Zimmermann Telegram http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/zimmermann/

This Day in History: Apr 6, 1917: U.S. enters World War I. History.com. http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/us-enters-world-war-i

This Day in History: June 28, 1914: Archduke Franz Ferdinand assassinated. History.com http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/archduke-franz-ferdinand-assassinated

Travis, Alan. “Lusitania divers warned of danger from war munitions in 1982, papers reveal,” The Guardian, April 30, 2014 . http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/01/lusitania-salvage-warning-munitions-1982

USS Leviathan. Department of the Navy – Naval Historical Center. http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/sh-usn/usnsh-l/id1326.htm

WWI Casualty and Death Tables, PBS. http://www.pbs.org/greatwar/resources/casdeath_pop.html

WWI Timeline, PBS. http://www.pbs.org/greatwar/timeline/time_1914.html

Zieger, Robert H.. America’s Great War: World War I and the American Experience. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2000.

Ziegler-McPherson, Christina A. Immigrants in Hoboken: One-way Ticket, 1845-1985. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011

This digital history page was created for the Hoboken Historical Museum by Darian Worden, July 25, 2014.