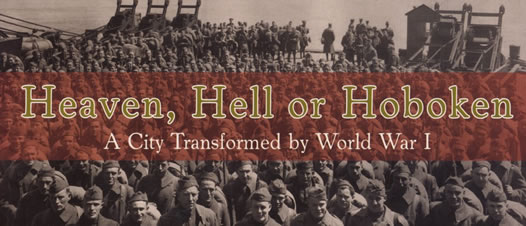

Heaven, Hell or Hoboken: A City Transformed by World War I

September 2008 – January 2009

The designation as a port of embarkation meant national fame for Hoboken – General John J. Pershing’s promise to the troops that they’d be in “Heaven, Hell or Hoboken” by Christmas of 1917 became a national rallying cry for a swift end to the war, which actually dragged on for another year. But it also meant economic hardship for the small city after the federal government seized Hoboken’s piers and the German shipping lines that were major employers, closed most of its bars and beer gardens, and displaced or interned hundreds of German nationals who were not yet naturalized U.S. citizens as “enemy aliens.”

Between June 1917 and November 1918, some 1.5 – 2 million soldiers passed through Hoboken, but most were fed and housed by the U.S. military, while local businesses saw the local population decline and the city saw its revenues drop sharply. At the time, German citizens and Americans of German descent made up about 25 percent of Hoboken’s population, far outnumbering the next largest immigrant groups, Irish and Italians.

The exhibit tells the story through research and talks by Christina Ziegler-McPherson and other historians, as well as through personal letters and artifacts of soldiers and residents of Hoboken. Director Bob Foster and collections manager David Webster assembled displays from the Museum’s collections and other sources, comprising uniforms, helmets, gas masks, rifles and other gear, as well as letters and photographs from Hoboken’s soldiers, 70 of whom lost their lives on the European battlefields. The exhibition includes Hoboken’s draft registration book, on loan from the City Clerk’s office. Also on view – government-sponsored posters and advertisements by prominent artists and illustrators exhorting Americans to contribute to the war effort, through volunteering, war bonds, and general morale-boosting.

Ziegler-McPherson explores the federal government’s struggle to build the infrastructure necessary to conduct the war, using a combination of persuasion, exhortation and coercion to drum up volunteers both to fight and to muster supplies and logistics for the effort. Most of the local draft boards, for example, were staffed by volunteers, as were the medical experts who examined the new recruits, she says. The government hired so-called dollar-a-year men, professionals who donated their time and expertise to the war effort. The Red Cross mobilized volunteers to help gather medical supplies. Sometimes, volunteerism went too far, however, according to Ziegler-McPherson, as large networks of self-appointed vigilantes developed, such as the “American Protective League,” which numbered some 10,000 members nationally, who opened mail and spied on neighbors in the name of helping the government identify possible German operatives.